Learning to Listen - my experience of making Zest's new show

/Zest Theatre are in the process of making a new show for young audiences. In the light of the recent increases in hate and xenophobia in our communities, we’re examining the theme of difference and our increasing fear of those ‘other’ to us. As part of this, we’re working in communities across the country to gather a whole range of voices and opinions. I joined the second and third week of the process as the Zest team visited 205 young people from communities in Lincolnshire, London and the North East. I have learnt so much about these communities during this time, but more then that, I have also learnt so much about myself.

How do you react to someone who thinks completely unlike you? Whose life experiences are beyond your own comprehension, and who seem to be threatening your entire way of life? I like to think that in these situations I would the bigger person, that I’d set aside differences and in doing so step up to the moral high ground. More often than not, though, if I am faced with a political opinion that conflict with my own my instinct is to insist that I am right and their viewpoint is incorrect, false or, when I’m erring on the dramatic side, abhorrent.

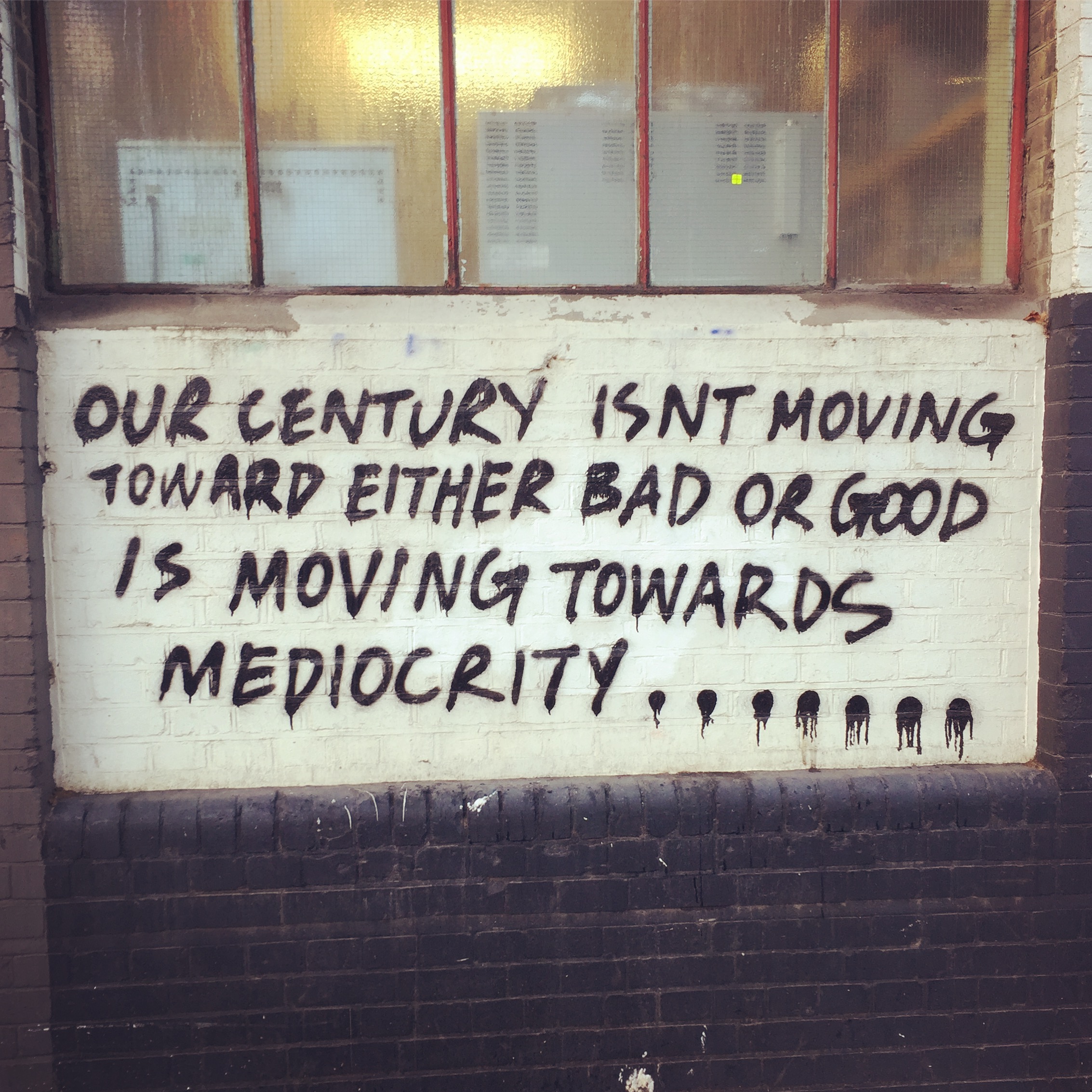

Unfortunately, I am hardly alone in this. In fact, the more polarized our social and political beliefs become, the less willing we become to set difference aside even for a moment. Our instinctive responses of judgement and animosity extinguish any chance of common understanding and we drive each other apart. The space that is left becomes a battle ground of political propaganda, news headlines, Facebook statuses and ‘facts’ that most of us will never seek to verify the credibility of.

Why do we react so strongly? Perhaps somewhere down the line we began to equate listening with agreeing. That if you disagree with someone and do not shut them down at every turn, then you are complicit in their views and are part of the problem. You aren’t doing your bit for your side of the fence if you’re willing to listen to the enemy. ‘Enemy’ might sound like a strong word, but, in a society that’s becoming more and more preoccupied with the idea of ‘us versus them’, it seems pretty apt.

It turns out that joining an R&D process for a show about difference, otherness and broken communities was the perfect opportunity for me to learn how to listen. I had never worked with the Zest team before and didn’t really know what to expect. I certainly didn’t expect that over the course of two weeks I would meet so many young people whose perspectives, ideas and beliefs were so different, and sometimes downright alien, to mine.

I was born and raised in Liverpool, a city proud of its immigrant heritage, a place that benefited massively from EU support and, as a result, had a majority vote in favour of Remaining in the EU. For university, I spent four years across the big Atlantic pond at a mostly very liberal university close to Boston, Massachusetts, that prides itself on its large international student population. To say I’ve spent most of my life in left-leaning communities would be a pretty fair comment.

Boston, England, on the other hand had the highest majority to vote Leave in the country at over 75% and a voter turnout of over 77%. We wanted to hear from this community and add their voice to the making of our show. We met with young people from Boston on the brink of being old enough to vote, but whose voices ultimately went unheard during the referendum. We spoke to a group of 15 students, all between the ages of 16-18 years old.

Zest is a Lincolnshire based theatre company and our director, Toby, has worked in and out of Boston for the last 10 years. This meant he had a real understanding of Boston’s community and how it has changed over the years. It was a different story for Luke and Laura (our actors) and myself though. To provide us with some context, Toby asked the group to explain their experiences growing up and living in Boston and how they felt about their town. The initial response was overwhelmingly focused on how stifling the town was, and how lack of jobs and opportunities meant that out of the 15 students, not a single one intended to stay settled in Boston.

From this point the conversation shifted to be about the East European migrant community that arrived after 2004. Boston is considered to be the most significant example of the effect of EU immigration in recent years with the population increasing from approximately 56,000 in 2001 to 65,000 in 2011 thanks to migrant workers.

To their credit, the Boston students were brave enough to share their honest opinions with us, negative or positive, and were open to our questions about why they felt the way they did. They talked to us about how stories shared by local newspapers and spread by word of mouth have negatively impacted their views of migrant workers, and how often they were hearing anti-immigrant rhetoric from older generations in the Boston community.

It was clear that there was tension between the historically white British members of the Boston community and the recent community additions from East Europe. We reached a point in our conversation where the students were beginning to unpack why this negativity between groups existed. For these young people, the idea of British-ness was about the things you do such as working hard and being polite, as well as referring to where you were born. They felt these attributes weren’t always exemplified by members of migrant communities.

In contrast we’d spent the previous day working with 70 young people from across East London during a Careers in Theatre day at Half Moon Theatre in Tower Hamlets. The diverse range of our London group was a direct contract to the group in Boston with only a small amount identifying as white British. In London responses were much more about heart, feelings and experiences: “I’m British because I love British food”, “I’m British because my mum tells me I am” or “I’m British because I love Britain”. For the group at Tower Hamlets, equal opportunity for everyone, good food, hard work and love of the country made being British great – not where you were born, where your parents or grandparents were born, what you looked like, or what language your family spoke. There was far less normalized scapegoating of non-British community members.

Interestingly, what became clear as we talked with our Boston group was that they had never really voiced any of these sentiments in their entirety out loud before. And because they’d never fully articulated how they felt, they’d never had the chance to reflect on what they thought. In addition, they had strong opinions on local issues but much less of an opinion on bigger issues such as Brexit or the very recent nomination of Donald Trump as the USA’s President-Elect.

If this had been any other conversation, I probably would have reverted to judgement at this point. How could anyone have such strong opinions on these local problems but not know anything about the more global news stories that have created them? But the point of our workshops with young people across wasn’t to change their minds or tell them that they’re wrong, it was to listen; to gain a genuine sense of how young people in Britain feel about their nation and about the world they are set to inherit. Ironically, if I’d had the chance to tell them everything that I felt about the world I would have talked all over the real heart of their problem.

“Who’s going to listen to us anyway?”, one student asked. It was the worst question we could have been asked, and that’s because there was no good answer. Who was going to listen? Why would they go to the trouble of learning about the world and developing your own informed opinion when you feel no one cares what you have to say anyway? Why learn about the EU referendum if you have no say in the matter? Why question the prejudices of your community if your community has no desire to change? We asked how they would fix the tension in Boston if we had a magical way of changing everything. Silence filled the room, until one young person simply said, “Well, its communication isn’t it”. Communication between both sides would change everything. But these young people had been ignored and devoiced by their country to the point where simple communication between different groups seems like an unattainable feat. Why believe you have the power to change the world if you’ve never seen any proof that you can?

Through all this talking and listening, Zest’s new production is slowly emerging. This new show is our response to the endless questions facing the young people of Britain today. It’s a big and complicated topic, so we’ve decided to represent the macro socio-political climate of the nation with a micro domestic relationship of an estranged half brother and sister relationship. Inspired by the experiences and voices of young people across the country, we created the characters of Katie (17) and Callum (19), two young people who have a father in common and seemingly little else.

They are each other’s “other”: different ethnicity, different cities, different opportunities. When growing issues in his home life spur Callum to seek help from his estranged father, Katie and Callum are confronted with the bittersweet reality of the other’s existence. Their lives have nothing in common, so how could they possibly start to understand each other? How could Callum understand how fragile and suffocating the illusion of the upper middle class family is? How could Katie understand how it feels to be so desperate for help, but rejected by everyone? Life as they know it is at risk and the noise of the wider world feeds them images of opposition and mistrust, images say that in order to help others you have to lose something in return. Everything they experience tells them they can’t change the world.

But we believe young people can change the world and many of those we have met feel that way too! So we are building a show to tell young people across Britain that the personal is political, that their voices count and that change on the smallest scale has the power to effect communities for the better. We seek to encourage those who are already determined to change the world, and to show the disheartened that the first step to helping their communities heal and grow is to listen to each other and have faith that their voices will be heard.

In January we return to Half Moon to conclude this stage of the R&D, we’ll keep you posted on how it goes.